A Day in Venice

June 8, 2016

By Wendy Atwell

I was feeling shabby as I followed our chic guide up the stairs of the Doge Palace. The Scala d’Oro ascends in a lavish profusion of carved marble, painting and gilding. But, step after step, this unworldly radiance did nothing to help my burning muscles. I was suffering from a mix of jet lag and too much wine for lunch and dinner the day before, all topped off with an irresistible nightcap.

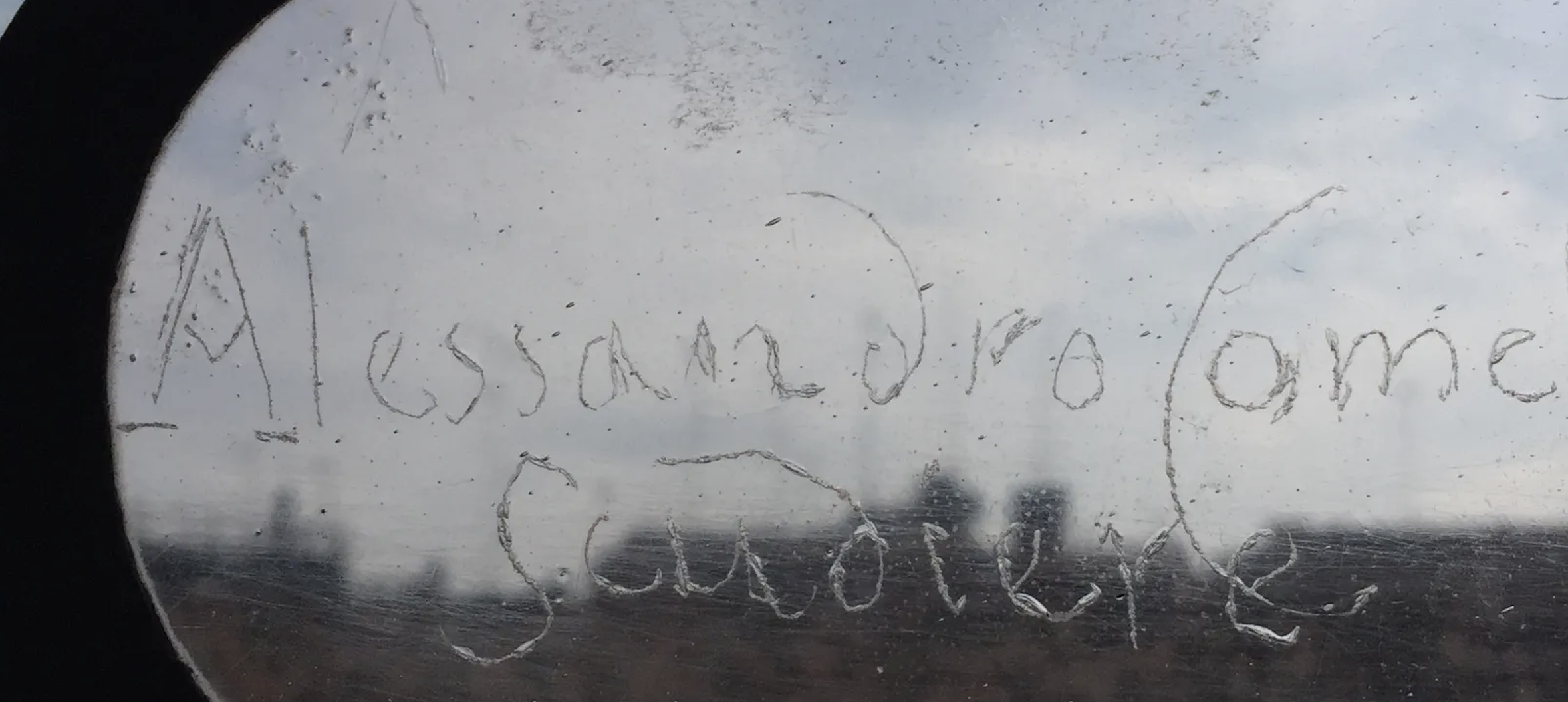

When we finally reached the second floor, our guide showed us graffiti from the year of 1736. The bodyguards had etched into the beautiful old windowpanes, while sitting outside the door, waiting for their important people. This, and the chance to stop, made me feel a little better. I could relate more to their derelict behavior than the grand immanence of the doges, aristocrats who were elected for life to rule the Most Serene Republic of Venice, a system that lasted for over one thousand years.

First overtaken by Napoleon, today Venice is conquered by tourists, creating a perverse mix of postcards and piazzas; selfie sticks and Byzantine murals. While the masses once followed their doge, today they follow tour guides wielding, for less noble purposes, bizarre scepters fashioned from an umbrella or a car antenna, trailing neon plastic tape.

The Venetians ruled by aristocracy and the offending doge had attempted to make his role an inherited position. But the wealthy elite who selected their leader only chose him as a representative leader of the group; he was not a king. The pristine white marble staircase shows no trace today of the extravagant mess his blood must have made, dripping down the steps. That was the point, of course, to make a big show of it, and after setting this example, they never had to do it again.

Our guide was born and raised in Venice, and she exuded a quiet pride of her city’s indomitable history. I am one of at least 60,000 tourists who flew across the ocean and dropped down into this ancient place. Seeped in history, Venice is an antidote to the meaningless void of suburbia, filled with air blowers and barren big box parking lots.

Yet my idealized view of Venice clashes with the reality. A giant billboard looms over the lagoon, covering the reconstruction of a building. A veil of garish commercialism has been cast over this magical cityscape. At the Bridge of Sighs, everyone wants a selfie. From our position inside the palace, we can see this claustrophobic’s nightmare from the other side. The bridge bears a clog of frenzied, eager photographers, each a star in her Instagram/Snapchat/Facebook feed.

From our privileged position inside the palace, we move, uninhibited, into the adjacent prison. There’s a formal wooden doorway located conveniently inside the doge’s chambers with stairs that led down to “the wells.” This was the older prison, but prisoners drowned down there, so they built another building next door, where juxtapositions abound. The only luxury seems to be the sunlight illuminating the bare walls and unadorned floors, slicing through the iron bars to peek into the dark crevices of human suffering. One guide who gave tours of the torture chambers recalled how some of her clients could feel the misery; supposedly they could smell, hear and taste it, ghosts short circuiting time through the senses.

The courtyard of the Doge’s Palace performs a survey of architectural history through the ages—the small, intimate medieval scale grows into the Renaissance’s grandiosity, and the Rococco’s illustriousness. Earlier in the morning on my run, I chased a giant cruise ship as it powered out to sea. The size of the ship eclipsed the entire Doge Palace, yet it’s not just the change in scale that has grown so astronomically; it’s the change in speed both physically and digitally, and everything is happening exponentially.

Across the Grand Canal, Tadao Ando’s restoration of the 17th century Customs House reframes the building into a piece of art itself. All ships sailing into port stopped here to pay customs and be inspected for quarantine. Some of the bricks look strangely white and soft; they are fuzzy with salt. Ando didn’t touch the walls but instead set his infrastructure apart so that it feels like we are floating inside history. This is the Punta della Dogana, home to the contemporary art collection of Francois Pinault. Accrohage, an exhibition curated by Caroline Bourgeois, features work from his collection.

On Kawara’s Sept. 13, 2001 shows a New York Times image from the 9/11 terrorist attacks. It’s one of the twin towers before it fell, with a giant gash in the building’s side where the plane went in, smoke bellowing from inside. Fifteen years later, this image reads like a rip in the fabric of time, a pivotal moment, forever distinguishing the way we were then with the way we are now.

Even so, time remains meted out in the same measure. In the bell tower overlooking Piazza San Marco, for every hour since 1499, the two bronze men have wielded their hammers, ringing the bell for 500 years. It’s only during the last one hundred years that a brutal modernity bloomed under the dark sun of two World Wars. Venice is also home to the modern art collection assembled by Peggy Guggenheim. She obtained much of her collection, such as Brancusi’s Bird, during fire-sale situations when artists desperately needed money to escape the Nazis.

The German painter Peter Dreher was 13 when WWII ended and deeply traumatized by the war. His series, Tag um Tag guter Tag, translates to “day after day, it is a good day,” a Zen Buddhist-inspired title. In 1974, he began a series of paintings that he has painted every day for over 40 years, accumulating over 5,000 paintings of a glass of water. The overall composition of the image remains the same, but the light changes with the day, along with small changes in the window dressing as seen reflected in the glass. To redirect his angst, Dreher performs a meditation, painting this image over and over again, creating a masterpiece of formal study and a practice of diligence. His steadied, focussed attention is mirrored in the simplicity and clarity of the subject.

My daughters and I are equally focussed but completely misdirected. With the Eat Italy app, I’m trying desperately to locate the home-made gelato. Misled by Google Map’s failing signals in the ancient, narrow alleyways, we walk in circles in an off-beat section of the city where the locals live.

We end our day in Piazza San Marco after dinner, in the hopes of avoiding the crowds, but still we dodge people, pigeons and now, also puddles. A scowling man hoists a red rose in my face, obliterating any possible trace of romance or chance of transaction. What is his story? How did he come to be here, selling roses, without understanding the point of a rose?

Inside Basilica San Marco, the ancient floors are bowing, but outside people are dancing with their shoes off, splashing in the water-filled piazza. We are all playing at the same game as the tide washes in.

When we finally reached the second floor, our guide showed us graffiti from the year of 1736. The bodyguards had etched into the beautiful old windowpanes, while sitting outside the door, waiting for their important people. This, and the chance to stop, made me feel a little better. I could relate more to their derelict behavior than the grand immanence of the doges, aristocrats who were elected for life to rule the Most Serene Republic of Venice, a system that lasted for over one thousand years.

First overtaken by Napoleon, today Venice is conquered by tourists, creating a perverse mix of postcards and piazzas; selfie sticks and Byzantine murals. While the masses once followed their doge, today they follow tour guides wielding, for less noble purposes, bizarre scepters fashioned from an umbrella or a car antenna, trailing neon plastic tape.

The Venetians ruled by aristocracy and the offending doge had attempted to make his role an inherited position. But the wealthy elite who selected their leader only chose him as a representative leader of the group; he was not a king. The pristine white marble staircase shows no trace today of the extravagant mess his blood must have made, dripping down the steps. That was the point, of course, to make a big show of it, and after setting this example, they never had to do it again.

Our guide was born and raised in Venice, and she exuded a quiet pride of her city’s indomitable history. I am one of at least 60,000 tourists who flew across the ocean and dropped down into this ancient place. Seeped in history, Venice is an antidote to the meaningless void of suburbia, filled with air blowers and barren big box parking lots.

Yet my idealized view of Venice clashes with the reality. A giant billboard looms over the lagoon, covering the reconstruction of a building. A veil of garish commercialism has been cast over this magical cityscape. At the Bridge of Sighs, everyone wants a selfie. From our position inside the palace, we can see this claustrophobic’s nightmare from the other side. The bridge bears a clog of frenzied, eager photographers, each a star in her Instagram/Snapchat/Facebook feed.

From our privileged position inside the palace, we move, uninhibited, into the adjacent prison. There’s a formal wooden doorway located conveniently inside the doge’s chambers with stairs that led down to “the wells.” This was the older prison, but prisoners drowned down there, so they built another building next door, where juxtapositions abound. The only luxury seems to be the sunlight illuminating the bare walls and unadorned floors, slicing through the iron bars to peek into the dark crevices of human suffering. One guide who gave tours of the torture chambers recalled how some of her clients could feel the misery; supposedly they could smell, hear and taste it, ghosts short circuiting time through the senses.

The courtyard of the Doge’s Palace performs a survey of architectural history through the ages—the small, intimate medieval scale grows into the Renaissance’s grandiosity, and the Rococco’s illustriousness. Earlier in the morning on my run, I chased a giant cruise ship as it powered out to sea. The size of the ship eclipsed the entire Doge Palace, yet it’s not just the change in scale that has grown so astronomically; it’s the change in speed both physically and digitally, and everything is happening exponentially.

Across the Grand Canal, Tadao Ando’s restoration of the 17th century Customs House reframes the building into a piece of art itself. All ships sailing into port stopped here to pay customs and be inspected for quarantine. Some of the bricks look strangely white and soft; they are fuzzy with salt. Ando didn’t touch the walls but instead set his infrastructure apart so that it feels like we are floating inside history. This is the Punta della Dogana, home to the contemporary art collection of Francois Pinault. Accrohage, an exhibition curated by Caroline Bourgeois, features work from his collection.

On Kawara’s Sept. 13, 2001 shows a New York Times image from the 9/11 terrorist attacks. It’s one of the twin towers before it fell, with a giant gash in the building’s side where the plane went in, smoke bellowing from inside. Fifteen years later, this image reads like a rip in the fabric of time, a pivotal moment, forever distinguishing the way we were then with the way we are now.

Even so, time remains meted out in the same measure. In the bell tower overlooking Piazza San Marco, for every hour since 1499, the two bronze men have wielded their hammers, ringing the bell for 500 years. It’s only during the last one hundred years that a brutal modernity bloomed under the dark sun of two World Wars. Venice is also home to the modern art collection assembled by Peggy Guggenheim. She obtained much of her collection, such as Brancusi’s Bird, during fire-sale situations when artists desperately needed money to escape the Nazis.

The German painter Peter Dreher was 13 when WWII ended and deeply traumatized by the war. His series, Tag um Tag guter Tag, translates to “day after day, it is a good day,” a Zen Buddhist-inspired title. In 1974, he began a series of paintings that he has painted every day for over 40 years, accumulating over 5,000 paintings of a glass of water. The overall composition of the image remains the same, but the light changes with the day, along with small changes in the window dressing as seen reflected in the glass. To redirect his angst, Dreher performs a meditation, painting this image over and over again, creating a masterpiece of formal study and a practice of diligence. His steadied, focussed attention is mirrored in the simplicity and clarity of the subject.

My daughters and I are equally focussed but completely misdirected. With the Eat Italy app, I’m trying desperately to locate the home-made gelato. Misled by Google Map’s failing signals in the ancient, narrow alleyways, we walk in circles in an off-beat section of the city where the locals live.

We end our day in Piazza San Marco after dinner, in the hopes of avoiding the crowds, but still we dodge people, pigeons and now, also puddles. A scowling man hoists a red rose in my face, obliterating any possible trace of romance or chance of transaction. What is his story? How did he come to be here, selling roses, without understanding the point of a rose?

Inside Basilica San Marco, the ancient floors are bowing, but outside people are dancing with their shoes off, splashing in the water-filled piazza. We are all playing at the same game as the tide washes in.