Bright Splinters:

Notes from Reality Hunger

Notes from Reality Hunger

May 20, 2016

By Wendy Atwell

May 12, 2016: After my daughter gets home from her first year of college, she has to have sinus surgery. We arrive at our assigned time, 7 AM, but they make us wait for an hour. The waiting room says “No Food or Drink” and is filled with anxious patients and relatives. Fox News blares from the overhead television, making it hard for me to read my book. A few feet away, a mother tries to entertain her young daughter. The daughter has special needs and she is unappeasable. The father just sits there looking angry.

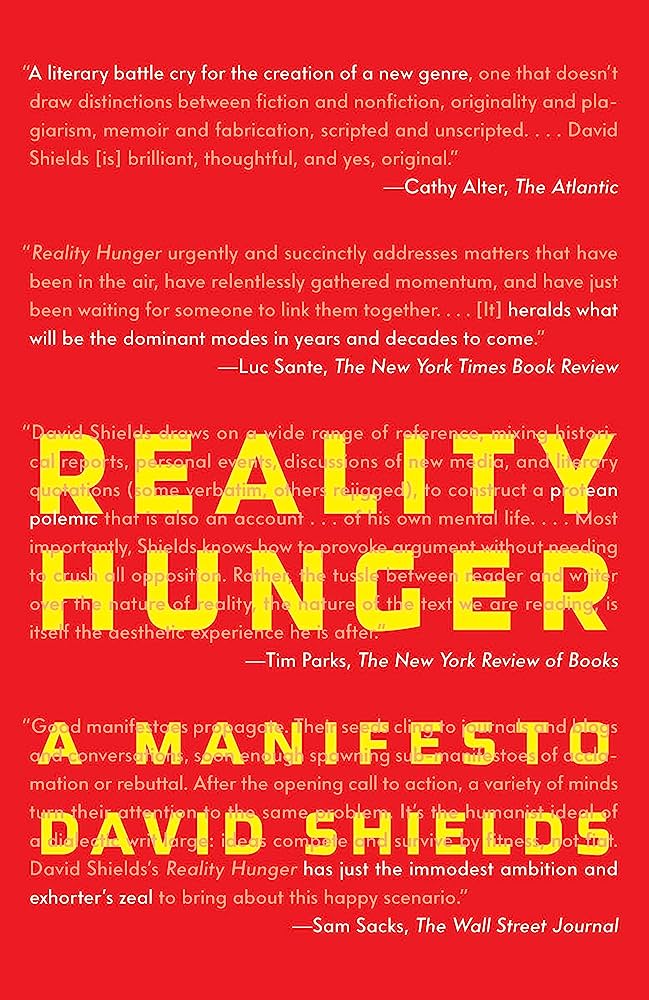

May 13, 2016: I’m starving. I order Bakery Lorraine’s Kale Caesar Salad and a salted caramel and chocolate tart to-go. Next door at the Twig, I buy Reality Hunger by David Shields. It’s a manifesto for a new style of writing, the anti-novel, more like a collage, which is reflective of today’s world. He lists his thoughts and ideas in numbers.

#319: “Conventional fiction teaches the reader that life is a coherent, fathomable whole that concludes in neatly wrapped-up revelation. Life, though–standing on a street corner, channel surfing, trying to navigate the web or a declining relationship, hearing that a close friend died last night–flies at us in bright splinters.”

The mother is trying to calm her daughter by letting her get up and run around the waiting room. When she can’t calm her down, she sits down next to me and calls her own mother. “I heard about the saga. I can’t believe she did that.” I hear her mother’s voice clearly through the phone. Listening to them talk, I think how they sound just like me and my mother.

May 14, 2016: In David Shield’s class, I try to remember the type of cubism of my favorite collage at the McNay. Not analytic, but synthetic cubism, because the image gets formed from disparate elements. I remember how cutout pieces of paper form the shape of a guitar, and they are glued onto floral wallpaper.

My daughter was nervous before her surgery. Even though it was a simple, routine day surgery, she had watched too many episodes of Grey’s Anatomy. “It’s always the procedures where they’re not supposed to be worried about anything happening,” she said. I say my prayers. I recognize how superstitious I am to think, if we are saying these things, then nothing will happen. But if we don’t worry about these things, then something might happen.

2007: Kanye West’s mother died while getting a breast reduction and a tummy tuck.

#45o: “Whether we’re young, or we’re all grown up and just starting out, or we’re getting old, or getting so old there’s not much time left, we’re looking for company, and we’re looking for understanding: someone who reminds us that we’re not alone, and someone who wonders out loud about things that happen in this life, the way we do when we’re walking or sitting or driving, and thinking things over.”

Because her own daughter had lost control, and even as she continued to, the daughter had to call her mother.

May 19, 2016: I find the folder with my notes on cubism. September 21, 1995: over a year before my first daughter is born, in 20th C. European and US Art, an Art History class taught by Fran Colpitt at UTSA, I write:

May 19, 2016: I find the Picasso collage on the McNay website: Guitar and Wine GlassGuitar and Wine Glass, 1912, collage and charcoal on board.

#354 “In collage, writing is stripped of the pretense of originality and appears as a practice of mediation, of selection and contextualization, a practice, almost, of reading.”

Contemporary artist Pae White harvested spider webs and placed them against color fields, so that they looked like magic drawings. You had to look carefully to marvel at the details but the webs were framed, under glass, captured like a specimen.

#371 “Nonfiction, qua label, is nothing more or less than a very flexible (easily breakable) frame that allows you to pull the thing away from narrative and toward contemplation, which is all I ever wanted.”

More from Colpitt:

Rushing to exercise one morning, I see a spider web in my neighbor’s yard. It stretches from her brick wall and attaches to her garden shack. The morning’s sunlight is fresh golden pink like a peach and it shines at an angle that illuminates every strand. The web’s intricacy is staggering. I can see every fiber, and concentric circles of perfectly-spaced little dashes, revealing layers upon layers, a complex system designed to trap. I am caught.

#374: “You have to decide for yourself how to read its patterning, but if you pluck it at any point, the entire web will vibrate.”

Days later, after a heavy rainstorm, only the web’s infrastructure remains. I can see now that its fundamental structure is star-shaped. The variable angles are stretched out like the five-point stars we are taught to draw as children. When I was young, I tried to make a perfect one in pencil over and over again, but I could never draw a perfect star.

May 20, 2016: My father’s birthday, the second one since he died.

Before modernism, the painting acted like a window, revealing narrative scenes. But modernism rendered the picture plane flat into a two-dimensional space that does not make pretend attempts towards three dimensions.

My daughter draws well. I bet that she could make a perfect star. Or even if it wasn’t perfect, it would be stylized in a way that makes it into art.

1961: The year my husband was born, Ad Reinhardt described his black paintings:

#52: “Modernism ran its course, emptying out narrative.”

A family close to me is losing their father, the patriarch. He is on his deathbed; he has been for days. This makes me think about watching my own father die. People die from an infinitely vast array of causes, but I discover that the process of death remains the same. The hospice workers teach us how to look for the signs of death. I’m surprised at the relief this brings me, being able to grasp onto something that is universal and predictable.

#535: “I do not know if it has ever been noted before that one of the main characteristics of life is discreteness. Unless a film of flesh envelops us, we die. Man exists only insofar as he is separated from his surroundings. The cranium is a space traveler’s helmet. Stay inside or you perish. Death is divestment; death is communion. It may be wonderful to mix with the landscape, but to do so is the end of the tender ego.”

In Annie Dillard’s The Maytrees, when the husband is dying, the protagonist moves his bed outside, so he can die beneath the night sky, with the stars watching over him.

#34: “As recently as the late eighteenth century, landscape paintings were commonly thought of as a species of journalism. Real art meant pictures of allegorical or biblical subjects. A landscape was a mere record or report. As such, it couldn’t be judged by for its imaginative vision, its capacity to create and embody a world of complex meanings; instead, it was measured on the rack of its ‘accuracy,’ its dumb fidelity to the geography on which it was based. Which was ridiculous, as Turner proved, and as nineteenth-century French painting went on to vindicate: realist painting focused on landscapes and ‘real’ people rather than royalty.”

Every morning when I was growing up, I heard the NOAA weather radio blaring from my parent’s bathroom, a mechanized voice dictating the day’s forecast. The alienated machine twang of the voice became a soundtrack to my mornings. I tried to force a personality upon it, but my imposed character traits wouldn’t stick.

#82: “Art is not truth; art is a lie that enables us to recognize the truth.”

As my father lay dying, I sought solace from Thich Naht Hanh’s No Fear No Death. He talks about merging with the landscape–plum blossoms and little rainclouds–how the natural world exists and we are a part of it. How all we need is the awareness of this. I knew it wouldn’t help my father; nothing could, but I hoped for this epiphany. I thought about how Thay’s choice of metaphor mirrored my father’s lifelong obsession with rain.

#615: “What actually happened is only raw material; what the writer makes of what happened is all that matters.”

The way that Reinhardt described his paintings: “aware of no thing but art” makes me thing of Thay’s teachings about non-ego, makes me think of what I’m supposed to do while meditating, not think. To reach that something beyond that’s attainable only through this portal.

May, 2016 precipitation to date: 8.54″

Annie Dillard, The Maytrees, 215:

My father would be 75, but he stepped through this non-thinking, non-ego portal, absorptive like a black painting, out of space and time, somewhere on the other side of the stars in the night sky.

May 13, 2016: I’m starving. I order Bakery Lorraine’s Kale Caesar Salad and a salted caramel and chocolate tart to-go. Next door at the Twig, I buy Reality Hunger by David Shields. It’s a manifesto for a new style of writing, the anti-novel, more like a collage, which is reflective of today’s world. He lists his thoughts and ideas in numbers.

#319: “Conventional fiction teaches the reader that life is a coherent, fathomable whole that concludes in neatly wrapped-up revelation. Life, though–standing on a street corner, channel surfing, trying to navigate the web or a declining relationship, hearing that a close friend died last night–flies at us in bright splinters.”

The mother is trying to calm her daughter by letting her get up and run around the waiting room. When she can’t calm her down, she sits down next to me and calls her own mother. “I heard about the saga. I can’t believe she did that.” I hear her mother’s voice clearly through the phone. Listening to them talk, I think how they sound just like me and my mother.

May 14, 2016: In David Shield’s class, I try to remember the type of cubism of my favorite collage at the McNay. Not analytic, but synthetic cubism, because the image gets formed from disparate elements. I remember how cutout pieces of paper form the shape of a guitar, and they are glued onto floral wallpaper.

My daughter was nervous before her surgery. Even though it was a simple, routine day surgery, she had watched too many episodes of Grey’s Anatomy. “It’s always the procedures where they’re not supposed to be worried about anything happening,” she said. I say my prayers. I recognize how superstitious I am to think, if we are saying these things, then nothing will happen. But if we don’t worry about these things, then something might happen.

2007: Kanye West’s mother died while getting a breast reduction and a tummy tuck.

#45o: “Whether we’re young, or we’re all grown up and just starting out, or we’re getting old, or getting so old there’s not much time left, we’re looking for company, and we’re looking for understanding: someone who reminds us that we’re not alone, and someone who wonders out loud about things that happen in this life, the way we do when we’re walking or sitting or driving, and thinking things over.”

Because her own daughter had lost control, and even as she continued to, the daughter had to call her mother.

May 19, 2016: I find the folder with my notes on cubism. September 21, 1995: over a year before my first daughter is born, in 20th C. European and US Art, an Art History class taught by Fran Colpitt at UTSA, I write:

May 1912: Still Life with Chair Caning. transitional piece from analytical to synthetic Cubism. watershed piece for Cubism; dramatic breakthrough setting Cubism on path to synthetic; Picasso and Braque attempt to clarify images in their work; small, oval, surrounded by rope frame; further emphasis of painting’s objectivity. Cafe scene: scallop shell, lemon wedges, wine glass smoking pipe projecting out. JOU journal see that it’s newspaper. foreign materials. oilcloth printed to simulate chair painting first example of a collage: colle = glue; invention of collage

May 19, 2016: I find the Picasso collage on the McNay website: Guitar and Wine GlassGuitar and Wine Glass, 1912, collage and charcoal on board.

#354 “In collage, writing is stripped of the pretense of originality and appears as a practice of mediation, of selection and contextualization, a practice, almost, of reading.”

Contemporary artist Pae White harvested spider webs and placed them against color fields, so that they looked like magic drawings. You had to look carefully to marvel at the details but the webs were framed, under glass, captured like a specimen.

#371 “Nonfiction, qua label, is nothing more or less than a very flexible (easily breakable) frame that allows you to pull the thing away from narrative and toward contemplation, which is all I ever wanted.”

More from Colpitt:

use of cloth functions like letter to destroy window-ness; opaque; the object-ness. clue for a chair. glass table–seeing chair through glass proposes paradox between illusion and reality: fake chair caning (illusion) but cloth is real. layers of meaning that oilcloth proposes. legitimizes use of non-traditional art materials; this technique alters/opens up all possibilities for 20 c. art.

Rushing to exercise one morning, I see a spider web in my neighbor’s yard. It stretches from her brick wall and attaches to her garden shack. The morning’s sunlight is fresh golden pink like a peach and it shines at an angle that illuminates every strand. The web’s intricacy is staggering. I can see every fiber, and concentric circles of perfectly-spaced little dashes, revealing layers upon layers, a complex system designed to trap. I am caught.

#374: “You have to decide for yourself how to read its patterning, but if you pluck it at any point, the entire web will vibrate.”

Days later, after a heavy rainstorm, only the web’s infrastructure remains. I can see now that its fundamental structure is star-shaped. The variable angles are stretched out like the five-point stars we are taught to draw as children. When I was young, I tried to make a perfect one in pencil over and over again, but I could never draw a perfect star.

May 20, 2016: My father’s birthday, the second one since he died.

Before modernism, the painting acted like a window, revealing narrative scenes. But modernism rendered the picture plane flat into a two-dimensional space that does not make pretend attempts towards three dimensions.

My daughter draws well. I bet that she could make a perfect star. Or even if it wasn’t perfect, it would be stylized in a way that makes it into art.

1961: The year my husband was born, Ad Reinhardt described his black paintings:

A square (neutral, shapeless) canvas, five feet wide, five feet high, as high as a man, as wide as a man’s outstretched arms (not large, not small, sizeless), trisected (no composition), one horizontal form negating one vertical form (formless, no top, no bottom, directionless), three (more or less) dark (lightless) no–contrasting (colorless) colors, brushwork brushed out to remove brushwork, a matte, flat, free–hand, painted surface (glossless, textureless, non–linear, no hard-edge, no soft edge) which does not reflect its surroundings—a pure, abstract, non–objective, timeless, spaceless, changeless, relationless, disinterested painting—an object that is self–conscious (no unconsciousness) ideal, transcendent, aware of no thing but art (absolutely no anti–art).

#52: “Modernism ran its course, emptying out narrative.”

A family close to me is losing their father, the patriarch. He is on his deathbed; he has been for days. This makes me think about watching my own father die. People die from an infinitely vast array of causes, but I discover that the process of death remains the same. The hospice workers teach us how to look for the signs of death. I’m surprised at the relief this brings me, being able to grasp onto something that is universal and predictable.

#535: “I do not know if it has ever been noted before that one of the main characteristics of life is discreteness. Unless a film of flesh envelops us, we die. Man exists only insofar as he is separated from his surroundings. The cranium is a space traveler’s helmet. Stay inside or you perish. Death is divestment; death is communion. It may be wonderful to mix with the landscape, but to do so is the end of the tender ego.”

In Annie Dillard’s The Maytrees, when the husband is dying, the protagonist moves his bed outside, so he can die beneath the night sky, with the stars watching over him.

#34: “As recently as the late eighteenth century, landscape paintings were commonly thought of as a species of journalism. Real art meant pictures of allegorical or biblical subjects. A landscape was a mere record or report. As such, it couldn’t be judged by for its imaginative vision, its capacity to create and embody a world of complex meanings; instead, it was measured on the rack of its ‘accuracy,’ its dumb fidelity to the geography on which it was based. Which was ridiculous, as Turner proved, and as nineteenth-century French painting went on to vindicate: realist painting focused on landscapes and ‘real’ people rather than royalty.”

Every morning when I was growing up, I heard the NOAA weather radio blaring from my parent’s bathroom, a mechanized voice dictating the day’s forecast. The alienated machine twang of the voice became a soundtrack to my mornings. I tried to force a personality upon it, but my imposed character traits wouldn’t stick.

#82: “Art is not truth; art is a lie that enables us to recognize the truth.”

As my father lay dying, I sought solace from Thich Naht Hanh’s No Fear No Death. He talks about merging with the landscape–plum blossoms and little rainclouds–how the natural world exists and we are a part of it. How all we need is the awareness of this. I knew it wouldn’t help my father; nothing could, but I hoped for this epiphany. I thought about how Thay’s choice of metaphor mirrored my father’s lifelong obsession with rain.

#615: “What actually happened is only raw material; what the writer makes of what happened is all that matters.”

The way that Reinhardt described his paintings: “aware of no thing but art” makes me thing of Thay’s teachings about non-ego, makes me think of what I’m supposed to do while meditating, not think. To reach that something beyond that’s attainable only through this portal.

May, 2016 precipitation to date: 8.54″

Annie Dillard, The Maytrees, 215:

Lou wondered where his information would go when he died. Would filaments of learning plant patterns on earth? Would his brain train the sinking plankton to know their way around the seafloor from here to Stellwagen Bank? Her brain would deliquesce too, and with it all that she had learned topside….Bacteria would unhook her painstakingly linked neurons and fling them over their shoulders and carry them home to chew up for their horrific babies.

My father would be 75, but he stepped through this non-thinking, non-ego portal, absorptive like a black painting, out of space and time, somewhere on the other side of the stars in the night sky.